International News

Part 4: The complex history of Islamic extremism and Russia’s contribution to the rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS

Part four of a ten part series explaining how a series of events starting in 1951 led to the creation of Al Qaeda and ISIS, and their mid-21st century resurgence.

This is part four of a ten-part series that explains the rise of modern Islamic extremism. From 1951 to 2021, a series of key geopolitical events, many independent of each other, caused the Islamic Revolution, the rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS, the creation and collapse of the caliphate, and the reconstitution of ISIS as ISKP. While Western influence and diplomatic blunders are well documented through this period, the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation are equally culpable. The editors would like to note that a vast majority of the 1.8 billion people who are adherents to some form of Islam are peaceful and reject all forms of religious violence.

Read Part Three: The complex history of Islamic extremism and Russia’s contribution to the rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS

State-sanctioned violence grows in Afghanistan as the Soviets prepare to withdraw

Moscow forces the replacement of their puppet leader in Afghanistan and struggles to find an exit

When the Soviets assassinated Hafizullah Amin on December 27, 1979, and installed Babrak Karmal as their puppet leader, KGB head Yury Andropov advocated for Mohammad Najibullah to be installed as the head of the state security services of Afghanistan—the KHAD. After his appointment, Andropov immediately started an influence campaign to convince Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and Amin to support expanding Najibullah’s power, which earned him a seat in the Afghanistan Politburo.

When Najibullah took over the KHAD in 1980, he was responsible for 120 people. Six years later, the KHAD was an independent government Ministry with 30,000 highly paid employees trained by KGB advisors. Most of the KHAD budget came from the Soviet Union, and shortly after Andropov became the General Secretary of the Soviet Union in November 1983, he started laying the groundwork to replace Karmal with his protege, Najibullah.

During the six years Najibullah led the KHAD, the KGB funded and trained its staff. Over 16,000 extrajudicial executions were carried out, and 100,000 were imprisoned. The KHAD brutally tortured peasants and tribesmen, burned villages, killed livestock, and destroyed crops in an attempt to identify members of the mujahadeen. In the cities, anti-communists, intellectuals, professors, doctors, and educated professionals were threatened, assassinated, falsely imprisoned, and executed. Flush with funds from the Soviet Union and under Najibullah’s leadership, the KHAD was wildly corrupt.

When Mikhail Gorbachev became the Soviet Premier in 1985, he continued to follow the path created by Andropov, believing that after the Soviet withdrawal, Najibullah would be a stronger leader who would stay loyal to Moscow. The Main Defense Intelligence Directorate of the Soviet Union (GRU) disagreed. In their assessment, Najibullah would be even more polarizing than Karmal and would not be able to build a strong coalition with the various Afghan tribal warlords. Gorbachev was unmoved.

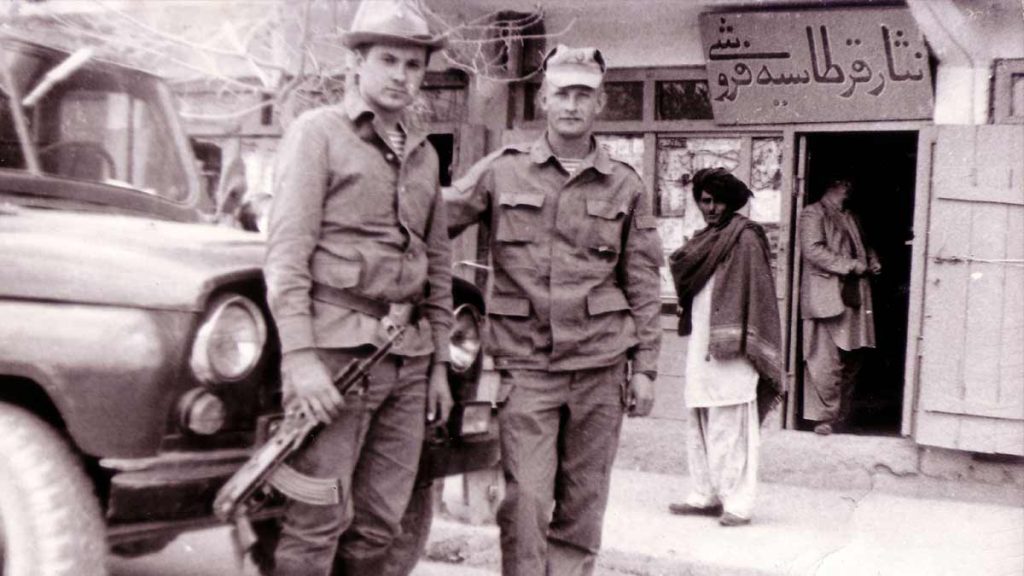

Soviet Union soldiers in Kabul, Afghanistan -1986

Credit – Photographer unknown – public domain

Moscow hoped that their newly installed leader could bring the fractured Afghanistan nation to reconciliation, ending eight years of violence, allowing the exit of Soviet troops, and keeping a pro-Soviet government in place. On May 4, 1986, Najibullah was made the General Secretary of the Afghanistan Politburo, with Karmal remaining as the Chairman of the Revolutionary Council. The assessment by the GRU that ethnic Uzbeks, Tajiks, and Pashtuns would resist cooperating with Najibullah, and the armed factions fighting against Soviet troops would reject him was accurate. Additionally, Karmal fought back, openly questioning Najibullah’s loyalty to Afghanistan, exposing his trail of corruption, and spreading misinformation.

Najibullah complained to Moscow that Karmal was interfering with his rule and asked for guidance, with Gorbachev deciding on a non-violent solution. In November 1986, Karmal was dismissed from the Revolutionary Council and exiled to Moscow. The Kremlin now saw the reconciliation strategy as a failure and decided that negotiating peace was the best option. Gorbachev also believed that due to the improving relationship with the United States, he could push for more favorable terms.

In March 1987, the first round of U.N.-sponsored peace talks between Pakistan and Afghanistan was held in Geneva, Switzerland, with the U.S. and the Soviet Union as guarantors. Pakistan negotiators refused to meet with the Afghanistan delegation because they did not recognize the Soviet-backed and controlled government as legitimate. The first round of negotiations failed, with Pakistan refusing to agree to a 16-month timetable for a controlled withdrawal of Soviet troops, demanding it be eight months. Additionally, the Soviets asked for the immediate end of U.S. arms shipments and financial support to the Afghan resistance as a condition for Soviet withdrawal. Washington refused.

In July, Najibullah made a secret trip to Moscow to meet with Gorbachev. The Soviet leader pressed him to make additional government reforms, hoping that the dead reconciliation plan could be brought back to life. Gorbachev’s council was undermined by the KGB, who advised against implementing some of his recommended reforms. Returning to Afghanistan, Najibullah announced that single-party rule would end. However, there were tight restrictions on what platforms would be acceptable. New parties were required to want to maintain relations with the Soviet Union, had to be Muslim, and had to oppose colonialism, imperialism, Zionism, racial discrimination, apartheid, and fascism. The mujahadeen and all but one armed faction fighting against the Soviet-backed Afghan government boycotted the August elections, but several new leftist parties were formed and were able to gain a handful of government seats.

In September, a second round of peace talks was held in Geneva. While progress was made in establishing the legitimacy of the Afghan government, no progress was made in establishing a timetable for the Soviet withdrawal, and the U.S. again refused to end military and financial aid before the Soviet troop withdrawal was complete.

In November, during the conference of the Afghanistan Politburo, Najibullah proposed accelerating the timetable for the Soviet withdrawal from 16 months to 12. A new constitution was approved, creating the office of the President. On November 30, Najibullah, running unopposed, was elected president of Afghanistan. Under the mandate of the new constitution, the Revolutionary Council would be dissolved and replaced with a General Assembly elected by the people.

On February 8, 1988, Soviet negotiators announced a conditional date of withdrawal from Afghanistan, hoping that the U.S. would agree to the immediate end of military and financial aid to the Afghanistan rebels. Washington rejected the proposal. With the domestic situation in the Soviet Union deteriorating, Gorbachev decided that an unfavorable peace deal was better than remaining in Afghanistan.

On April 14, Pakistan, Afghanistan, the Soviet Union, and the U.S. signed the Geneva Accords. Pakistan and Afghanistan agreed to non-interference and non-intervention, and Pakistan agreed to stop the flow of weapons across its border. The Soviet Union agreed that the withdrawal of the 40th Combined Arms Army would begin on May 15 and be completed by February 15, 1989. The U.S. did not have to end military and financial aid before the completion of the Soviet withdrawal.

On February 15, 1989, the last column of BTR-80 armored personnel carriers of the Soviet 40th Combined Arms Army crossed the Friendship Bridge into Soviet Uzbekistan. General Boris Gromov symbolically walked behind the troops, becoming the last Soviet soldier to withdraw from Afghanistan. Mobbed by reporters, he cursed profusely, later explaining that his anger was directed at “the leadership of the country, at those who start the wars while others have to clean up the mess.”

The Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan elevates Osama bin Laden to a cult of personality

There are questions about how much combat Osama bin Laden was engaged in with the mujahedeen, but he did participate in a handful of tactical battles. During his time in Pakistan and Afghanistan, bin Laden used his wealth and influence to promote victories on the battlefield and recruit Arabs to the Islamic cause within Afghanistan. While bin Laden was media-shy, his talent as a leader was well-known in the Middle East, converting his influence into a cult of personality.

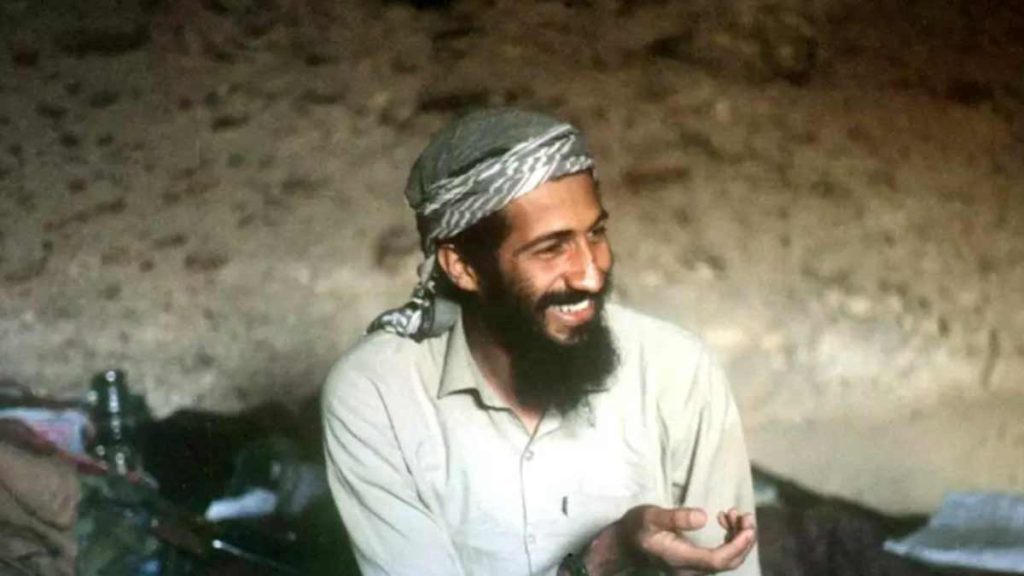

Osama bin Laden -1988

Credit – Photographer unknown – public domain

But bin Laden was looking ahead to the future. In 1988, shortly after the signing of the Geneva Accords, he quietly founded Al Qaeda. For him, Afghanistan was the end of the beginning. Al Qaeda would continue its violent jihad against what he perceived were the enemies of fundamentalist Islam and fight to establish Muslim states controlled by Sharia law.

Despite fighting against the Soviet Union, a lot of bin Laden’s beliefs were influenced by his exposure to Soviet propaganda, including late 19th Century Eastern European and Imperial Russia antisemitism. In the simplest of terms, bin Laden believed that Muslim Arabs faced four enemies: the Jews and Israel, the United States, “heretics,” and Shia Muslims, particularly Iranian Shias.

At the time of the Soviet withdrawal, bin Laden believed that the West had wronged Arabs and Muslims worldwide. The Al Qaeda charter established that the people of democratic nations directly participate in their government, making them legitimate military targets due to their complicity in their government decisions. Further, any “good Muslim” civilian who was killed due to their proximity to an attack would be blessed in death and go to paradise.

In 1989, bin Laden returned to Saudi Arabia and was given a hero’s welcome along with his Al Qaeda Arab Legion. He continued to lead a triple life, running aspects of the family construction business, continuing to work with Pakistan and Saudi Arabian intelligence agencies, and indirectly and directly supporting jihadist activity in Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

Bin Laden would return to Afghanistan to personally lead up to 800 Al Qaeda fighters in Operation Jalalabad, which was an attempt to install a pro-Pakistani mujahadeen government in Kabul. Although Soviet troops had withdrawn from Afghanistan, military aid to the Najibullah government continued. Moscow sent approximately $4 billion in weapons and ammunition, including OTR-21 Tochka-U short-range ballistic missile launchers with Scarab missiles and Su-27 multirole fighter aircraft.

Operation Jalalabad was a complete failure, with the Afghan army using its arsenal to stop the offensive. Up to 500 of bin Laden’s militants were killed, and he was forced to return to Saudi Arabia, further imbittered by another betrayal.

Once back in Saudi Arabia, bin Laden supported opposition movements against the Saudi royal family and ordered the executions of the leaders of the Soviet-backed Yemeni government. He also interfered with reunification talks in Yemen, which has led to decades of civil war, famine, and hundreds of thousands of deaths. The unrest continues to this day, with north Yemini rebels switching from Al Qaeda-oriented dogma to gaining support from the Islamic Republic Guard Corps (IRGC) of Iran. Today, the IRGC-backed Houthi rebels control approximately 30 percent of Yemen and have interfered with global shipping since November 2023 in support of the Hamas-initiated war against Israel.

The increasing influence of bin Laden and his meddling in Saudi government affairs drew the attention of King Fahd and the ire of the then-President of Saudi Arabia, Ali Abdullah Saleh. They now viewed bin Laden as more than a problem they could manage—he was becoming a threat.

The Saudis weren’t the only country warily watching bin Laden and the Al Qaeda Arab Legion. U.S. intelligence was also hearing chatter that his plans weren’t just contained to the Greater Middle East.

It was now 1990, and in less than two years, the first attempted Al Qaeda terror attack on U.S. soil would be stopped, and the Saudi government would send bin Laden into exile.

Over the last four chapters, we’ve outlined a number of events that individually, are completely disconnected. However, in 1991, all roads from the Soviet Union, the U.S., Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and Afghanistan converge to Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda. The only thing missing was the final spark. Iraqi President Saddam Hussein was preparing to light that fire.

Tomorrow’s installment: Iraq invades Kuwait, sparking the First Gulf War. The Saudi Royal Family rejects a plan by Osama bin Laden, sending him into exile. The Soviet Union starts to collapse and the Kremlin starts another war.

Read Part Four: The complex history of Islamic extremism and Russia’s contribution to the rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS