International News

Part 7: The complex history of Islamic extremism and Russia’s contribution to the rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS

Part seven of a ten part series explaining how a series of events starting in 1951 led to the creation of Al Qaeda and ISIS, and their mid-21st century resurgence.

This is part seven of a ten-part series that explains the rise of modern Islamic extremism. From 1951 to 2021, a series of key geopolitical events, many independent of each other, caused the Islamic Revolution, the rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS, the creation and collapse of the caliphate, and the reconstitution of ISIS as ISKP. While Western influence and diplomatic blunders are well documented through this period, the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation are equally culpable. The editors would like to note that a vast majority of the 1.8 billion people who are adherents to some form of Islam are peaceful and reject all forms of religious violence.

Read Part Six: The complex history of Islamic extremism and Russia’s contribution to the rise of Al Qaeda and ISIS

Vladimir Putin and George W. Bush become partners in the ‘War Against Terror’

The Rise of Al Qaeda

The first al Qaeda plot to attack the United States was uncovered in November 1990 when the FBI arrested operatives who were planning to blow up skyscrapers and government buildings. It would be an aspiration that Osama bin Laden would maintain for 11 more years.

In 1992, two bombs tore through Aden, Yemen, intending to target United States troops staying at the Gold Mohur and Aden Movenpick Hotels. In the first bombing, the small group of troops had already left for Somalia, and in the second, the bomb went off prematurely.

Then, on February 26, 1993, a truck bomb exploded in the underground parking garage of the World Trade Center in an attempt to topple the towers. The blast caused extensive damage, killing six and wounding over 1,000. Officially, Al Qaeda didn’t order the attack, but the chief architect, Ramzi Yousef, was trained by the terrorist organization.

Heavy equipment excavating the site of the World Trade Center parking garage bombing – February 1993

Credit – Photographer unknown – public domain

The group involved in the planning and execution was exposed when Mohammad Salameh, who rented the truck used to deliver the bomb, returned to the rental agency in New Jersey trying to get his $400 cash security deposit back.

The Saudi government accused bin Laden of being behind a November 1995 bombing in Riyadh that killed five American and two Indian soldiers and wounded 60. Three years later, two bombings targeting the U.S. embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, killed 224 and wounded more than 5,000 people.

The Millennium Plots and 9/11

Each successful attack drew more money and members to Al Qaeda’s ranks. A wave of terror that was planned for the year 2000 New Year celebrations, dubbed the Millennium Attack Plots, was mostly thwarted, partially by luck.

Jordanian officials uncovered a plot to attack four locations during New Year, including the Radisson Hotel in Amman, the Christian church on Mount Nebo, the border crossing between Israel and Jordan, and a holy site on the Jordan River where it is believed profit John the Baptist baptized Jesus of Nazareth. One of the plotters was Al Qaeda operative Abu Musab al Zarqawi, who would go on to be the founder of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

On December 12, 1999, Jordanian security forces arrested 16 people involved with the plot, eventually putting 28 people on trial. However, Al Zarqawi fled to Pakistan before he could be arrested. Twenty-two defendants were found guilty of the plot, including six with Al Qaeda, who were all sentenced to death. Another architect of the plot, Saudi national Abu Zubaydah, was the mastermind behind attacks planned in the United States.

Algerian national Ahmed Ressam traveled from Montreal, Canada, and attempted to enter the United States on a ferry through Port Angeles, Washington. Ressam raised suspicion among customs officials who searched his car and found enough explosives to produce four small bombs, timers, and detonators. He was arrested on December 14, 1999, and told investigators that Zubaydah was orchestrating the bombing of LAX Airport in Los Angeles under the order of bin Laden. Further investigation found that the Space Needle in Seattle, the Transamerica Tower in San Francisco, and Ontario Airport in the Los Angeles area were also planned targets.

On the other side of the world, Al Qaeda operatives hijacked Indian Airlines Flight 814 on December 24, 1999, and crisscrossed the Greater Middle East for a week, stabbing one passenger to death, a German, and wounding 17 others. The Indian government gave in to their demands, releasing convicted Al Qaeda-aligned terrorists Maulana Masood Azhar, Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, and Mushtaq Ahmed Zargar. Sheikh would go on to be one of the chief planners of the 9/11 attacks on the United States. Over the next 20 years, Azhar would lead three terror attacks in India, killing hundreds.

On New Year’s Eve in Syrian-occupied Lebanon, 300 members of the terror group Takfir wal-Hijra secured dozens of villages in northern Lebanon, attempting to establish the first Sharia law-based caliphate in the mountainous region. Over 13,000 troops were deployed to quell the uprising with fighting continuing until January 6, 2000. Twenty-five terrorists were killed, and another 55 were captured. Bin Laden was credited with financing Takfir wal-Hijra through shell companies and a bank in Beirut. The surviving fighters who escaped disappeared into the Palestinian refugee camp in Ain al-Hilweh, Lebanon. The 55 who were captured were sentenced to ten years to life in prison, with all receiving pardons in 2005.

The rift between al Qaeda and those who sought an even stricter interpretation of Shari law may go back as far as the mid-1990s. It is alleged that an offshoot of Takfir wal-Hijra in Sudan plotted to assassinate bin Laden in 1995 due to his liberal views on Sharia law and the formation of a caliphate. Despite the rift, the group led over a dozen terror attacks in Africa in coordination with Al Qaeda, mostly in Sudan.

The last part of the plot was an attack on the Arleigh Burke-class Aegis guided-missile destroyer USS The Sullivans on January 3, 2000, while it was refueling at the Yemeni port of Aden. The attack failed because the small boat, loaded with over 400 kilograms of plastic explosives, sank due to the amount of weight in the bow.

Damage to the guided-missile destroyer USS Cole after the October 12, 2000, Al Qaeda terrorist attack in Aden, Yemen

Credit – Photographer unknown – public domain

Al Qaeda learned from its mistake and, on October 12, attacked the guided-missile destroyer USS Cole while it refueled at Aden. Two small fiberglass boats were used, distributing more than 450 kilograms of C4 plastic explosives, and each only had a single suicide bomber onboard. Both boats struck the Cole, tearing a 40-foot-long gash into the port side and sparking a large fire. Seventeen crew members were killed and 39 wounded, and it took three days for damage control to stabilize the ship. U.S. officials would later find the Sudanese government to be complicit in working with Al Qaeda and seized over $13 billion in assets.

Eleven years after the first al Qaeda plot to destroy American skyscrapers was uncovered, bin Laden would achieve his goal. On September 11, 2001, two hijacked commercial airliners struck both towers of the World Trade Center in New York, collapsing the buildings. A third hijacked aircraft struck the Pentagon, and a fourth crashed in Pennsylvania when passengers tried to regain control. The attacks killed 2,996 and wounded over 6,000. Two decades later, hundreds more would die from illnesses attributed to the 9/11 attacks.

Initially, bin Laden denied any involvement in the 9/11 attacks, but in 2004, as part of a brief manifesto, he wrote, “God knows it did not cross our minds to attack the Towers, but after the situation became unbearable—and we witnessed the injustice and tyranny of the American-Israeli alliance against our people in Palestine and Lebanon—I thought about it. And the events that affected me directly were that of 1982 and the events that followed—when America allowed the Israelis to invade Lebanon, helped by the US Sixth Fleet. As I watched the destroyed towers in Lebanon, it occurred to me to punish the unjust the same way: to destroy towers in America so it could taste some of what we are tasting and to stop killing our children and women.”

A thirst for revenge fuels Vladimir Putin’s ascendency

When the Red Terror and Soviet Famine ended in 1922, the Soviet Union entered a brief period of reform which ended some of the oppressive Tzarist policies. Vladimir Lenin, who was already in declining health, eased restrictions on the Soviet republics, allowing them to reembrace their original culture, including language, religion, and art. Individuals were permitted to have small businesses within the guidelines of the Soviet government, blending Communism and Socialism.

The economy started to improve, and after decades of repression, deportations, war, famine, revolution, and civil war, the new Soviet society appeared to be finding its feet. All of this came to an end in late 1924 when Joseph Stalin became the Secretary-General, despite Lenin’s warnings. Seventy-five years later, history wouldn’t repeat, but it would rhyme.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the newly created Russian Federation entered a tumultuous period. Moscow struggled to contain inflation and wild swings of the rouble. The new country would face the 1993 Constitutional Crisis, and the economy would collapse in 1994 and 1998. For the connected and the bold, the underlying chaos was an opportunity for those seeking wealth and the growth of organized crime. However, unlike the turmoil of the Depression and Prohibition Era in the United States, where organized crime bosses fought over the control of bootleg alcohol, gambling, and illegal weapons, the new oligarch class fought for control of the now privatized industrial sectors of Russia—coal, steel, oil and gas, grain, construction, heavy equipment, and technology. Fueled by endemic government corruption, the Yeltsin administration and the now weakened state security services not only ignored the Game of Thrones happening in open view but, for the right price, participated in it. One of the men who grew allies during this period was the now-former KGB agent Vladimir Putin.

In 1991, an embittered Putin resigned from the KGB, refusing to work for the newly created Federal Security Agency (AFB). President Yeltsin dissolved the KGB in November 1991 in response to a failed coup d’etat that was led by Soviet hardliners earlier in the year, including the head of the KGB, Vladimir Kryuchkov. Yeltsin would go on to sign two more decrees, one creating the Ministry of Security of the Russian Federation in January 1992 and the second in December 1993, forming the Federal Counterintelligence Service of the Russian Federation (FSK). Each decree further eroded the legacy power structure created by the KGB.

Putin returned to his native home of St. Petersburg and, using information the KGB had gathered during the Soviet era, blackmailed Mayor Anatoly Sobchak to gain a job in the city government. He started as a reformer in name only, investigating corruption, but in reality, he was Sobchak’s political strongman.

Putin’s career was unremarkable until 1994 when he was named deputy mayor. He and Deputy Vladimir Yakovlev went on to run the city, with Putin building a circle of influence and earning future favors among the influential, wealthy, and the criminal underground. Sobchak’s initial popularity faded from 1995 to 1996 as public services deteriorated, crime increased, and allegations of corruption within the city government grew.

Putin became the local leader of the politically liberal and fiscally conservative Our Home–Russia Political Party in 1995 and ran the reelection campaign for Sobchak. Sobchak lost to his deputy Yakovlev in a close election, putting Putin out of a job. Sobchak would become the focus of a corruption investigation in 1997 and would flee to France.

Using his contacts and network, Putin moved to Moscow in early 1997 and was named the deputy chief of the Presidential Property Management Department. Less than a year later, he joined President Yeltsin’s staff and quickly maneuvered himself through a number of roles before becoming the leader of the FSK replacement, the 1995 Yeltsin-created Federal Security Service of Russia (FSB), on July 25, 1998.

Putin only led the FSB for 13 months, but he implemented a complete restructuring and dismissed almost all of the leadership, installing former Soviet-era KGB agents loyal to the ideals of Kryuchkov and his vision of restoring Russia to its former glory.

Like Lenin in 1922, Yeltsin was in declining health in 1998. Presidential elections were coming in less than two years, and potential candidates were starting to position themselves and build alliances. Within the Kremlin, Yeltsin’s inner circle started to warn him about Putin’s restructuring of the FSB, his growing influence and connections, and his desire to return to restore Soviet-style state controls. His aspirations were supported by a growing list of oligarchs, who viewed Putin as someone they could control while leveraging his vision of state security to grow and protect their wealth.

On August 9, 1999, Putin was appointed as one of three deputy prime ministers of the Russian Federation and endorsed by Yeltsin as his future successor in the upcoming 2000 elections. Eight days later, the State Duma confirmed Putin as the acting Prime Minister.

In the span of 2 1/2 years, Putin had gone from a failed St. Petersburg deputy mayor to the unelected prime minister of the second most powerful country on the planet. Even before Yeltsin’s endorsement, alarm bells were going off within the corners of the FSB and in the pages of the newly created free press about Putin and his plans.

To help his rise to power, Putin makes a series of deals with Islamic terrorist leaders

In the Sixth Part of this series, Chechen terrorist leader Shamil Basayev and his connections to Pakistan and Afghanistan and his encounters with organizations adjacent to Al Qaeda were lightly touched.

A young Basayev arrived in Azerbaijan in 1992 with an estimated 1,000 Chechen militants to fight in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, leading a call for jihad with Chechen leader Salman Raduyev. Basayev left for the Abkhazia region of Georgia in late 1992, while Raduyev continued to command the Chechen contingent. Reportedly, Basayev ordered the withdrawal from the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan in 1993 due to a series of military defeats and a lack of support for the call to jihad.

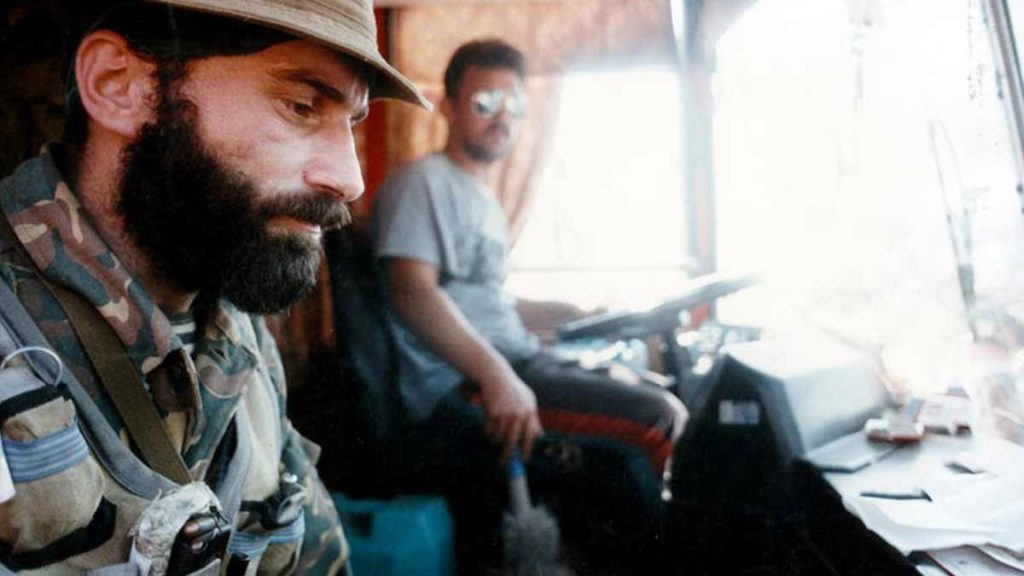

Chechen leader and terrorist Shamil Basayev – 1995

Credit – Photographer Natalia Medvedeva – public domain

Basayev would fight on the side of the Moscow-backed Abkhazia separatists, and he would go on to lead up to 1,500 volunteer fighters of the Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus (CMPC). Basayev is accused of overseeing the ethnic cleansing of Georgians in the breakaway Abkhazia Republic, the September 27 to October 11, 1993, Sukhumi Massacre, and grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions for the mass executions of captured Georgian soldiers.

This is where Basayev’s history becomes murky. He is believed to have defended Russian President Yeltsin during the failed August 1991 coup d’etat, occupying the barricades of the Russian White House with other Yeltsin supporters. There are many allegations that during the War in Abkhazia, Basayev and up to 200 Chechens within the CMPC received training and arms from the Main Defense Intelligence Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation (GRU). The CMPC would fall apart at the end of the War in Abkhazia, with different factions supporting the Moscow-backed breakaway republic and others aligning with Chechnya and other radical Islamic factions. And despite having a death warrant on his head, Basayev was able to freely travel between Chechnya, Georgia, and the Russian Federation.

Basayev would go on to run for president of Chechnya, coming in second place. He was then appointed deputy prime minister by newly elected president Aslam Maskhadov and actively worked to undermine his government. During a six-month period in which he was symbolically named the acting president of Chechnya, he gutted government oversight, shut down numerous ministries, and turned a blind eye to the theft of natural resources. By the end of 1998, Basayev was a warlord leading a rival faction against Maskhadov and had aligned himself with Afghanistan mujahideen veteran and Al Qaeda leader Ibn al-Khattab, a Saudi national. Al-Khattab had also broken away from President Maskhadov despite being named the Chief of Military Training for the Chechen Armed Forces in 1996.

Basayev met with Putin in March 1999 and agreed to help the Kremlin topple Maskhadov’s Chechen government and support a Russian invasion. Putin would reverse the failure of the First Chechen War with a quick success by taking just the northern third of the republic to the Terek River. Transcripts of phone records would show that Putin and his associates had numerous phone calls with almost a dozen radical Muslims and were using the FSB to orchestrate both kinetic and information warfare plans.

Al-Khattab and Basayev, along with Raduyev, openly called for the occupation of the Russian Federation Republic of Dagestan and the formation of a single state under Islamic Sharia law, declaring the final goal of expelling all Russians from the Caucasus. Putin had reached 20 years into the KGB past to tap the fears of long-dead Soviet leaders that Iranian-style radical Islam would spread to the Caucasus.

Independent of Putin’s plan, in April 1999, the Emir of the Islamic Djamaat of Dagestan (IDD), Bagauddin Magomedov, called for jihad to liberate “Dagestan and the Caucasus from the Russian colonial yoke” and created an unusual and doomed alliance. Magomedov and the IDD were aligned with Wahhabism, while Al-Khattab formed the Islamic Legion, comprised of foreign fighters, with a significant number aligned with the doctrine of Al Qaeda.

In July, Turpal-Ali Atgeriyev, the Deputy Prime Minister of National Security for Chechnya, and Deputy Prosecutor-General Adam Torkhashev traveled to Moscow to meet with Putin and warn him of the imminent invasion of Dagestan, which Putin was well aware of and counting on. Shortly after the Moscow meeting, an article in the Russian newspaper Moskovskaya Pravda warned that the Kremlin was preparing a series of false flag attacks in Moscow to undermine President Yeltsin and cited leaked documents.

The War in Dagestan and false flag attacks in Russia bring Putin to power

On August 4, the IDD launched its first attacks, and three days later, the Muslim Legion invaded the Republic of Dagestan. In an ironic twist, Basayev and al-Khattab were not greeted as liberators and instead were met with fierce resistance. Shortly after, President Yeltsin ordered the bombing of Chechnya. On August 19, newly minted acting prime minister Putin set a deadline for Russian forces to crush the rebellion by the end of the month. In the same speech, Putin threatened to start bombing Dagestani rebels “hiding in Chechnya.” In reality, airstrikes on Chechnya started on August 8, but the Kremlin didn’t acknowledge the bombings until August 26. By September 11, major fighting in Dagestan was over, and the Second Chechen War had started. What Basayev didn’t know is he had been double-crossed by Putin, who had cut another deal. He didn’t want a third of Chechnya; he was going to take it all.

Yeltsin and Putin intentionally delayed the response of Russian ground troops, preferring to let Dagestani forces exhaust themselves while prolonging the raids coming from Chechnya. By the end of August, a wave of terror attacks would spread across Russia, with history revealing the FSB executed most of them under the order of Putin.

The first attack was on August 31 at an arcade in the Manezh Square Shopping Mall in Moscow, adjacent to the Kremlin. Three phone calls allegedly from the Liberation Army of Dagestan took credit for the attack. Future investigations would blame the Islamic International Peacekeeping Brigade, an Islamist mujahideen organization co-created by al-Khattab and Basayev.

The next bombing was on September 4 in Buynaksk in Dagestan. The apartment building served as housing for Russian border guards and their families and was destroyed by a car bomb. Sixty-four people were killed, and another 133 were wounded. A second car bomb containing 2,700 kilograms of explosives was found by the Russian Army Hospital and defused.

On September 9, a bomb estimated to weigh 400 kilograms exploded in a Moscow apartment building. The nine-story brezhnevka was destroyed, killing 106 and wounding 249. The next day, Putin called United States President Bill Clinton and told him he was confident the bombing was executed by Chechen terrorists, adding that he believed the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Africa were not executed by Al Qaeda but by Chechnya.

At 5 a.m. on September 13, the next bomb exploded, destroying an eight-story apartment building, killing 119 and wounding 200. Due to poor planning, the false flag plot started to fall apart.

After the second bombing, Moscow businessman and landlord Achemez Gochiyaev had a horrifying realization. An acquaintance of his who was a former FSB agent had requested to rent the basement areas of four apartment buildings. The two blasts were in his buildings. Believing he was being set up, he contacted the Ministry of Internal Affairs, explaining what had happened and warning that bombs were likely in two more buildings. Moscow police searched the basements, finding massive bombs made of RDX.

As the smoke was still rising over the apartment block on Kashira Road, State Duma Deputy Gennadiy Seleznyov announced that there had been a third bombing in Volgodonsk in the Rostov-on-Don region of Russia. There had been no such explosion, but on September 16, a third bomb destroyed a nine-story brezhnevka in Volgodonsk, killing 17 and wounding 69.

On September 22, a man in the Russian city of Ryazan reported seeing two suspicious men carrying sacks into the basement of an apartment building from a car with partially obscured Moscow license plates. Police found 150 kilograms of white powder in three sacks with detonators and timers. Onsite testing identified the contents of the bags as the explosive RDX. The next day, Putin ordered the bombing of the Chechen capital of Grozny in response to the allegedly most recent attempted terrorist attack, declaring “no sympathy for the bandits.”

A quick investigation and telephone records traced the car and two men to a telephone number linked to the FSB office in Ryazan. The Ministry of Internal Affairs arrested three people who identified themselves as FSB agents from Moscow. Putin’s operation was in crisis, as Moscow had declared that the explosives were real to justify the bombing of Grozny. On September 24, the Kremlin declared the bags were filled with sugar, and the entire event was an FSB training exercise that ended in success due to the quick reaction of local authorities.

President Boris Yeltsin naming Vladimir Putin acting President of the Russian Federation – December 31, 1999

Credit – Press office of the Russian Federation – photographer unknown

Despite the obvious mistakes pointing to a government plot, Putin’s popularity soared. On December 31, Yeltsin resigned and named Putin acting President. Riding a wave of popularity due to the response to the so-called terror attacks and the initial success in Dagestan, Putin cruised to victory when Russians went to the polls on March 26, 2000.

Looking into Putin’s soul

The United States held elections in November 2000, and George W. Bush was elected the 43rd President in a contested election. On June 16, 2001, President Bush and President Putin met for the first time in Brdo Pri Kranju, Slovenia. Almost the entire world believed the Cold War was over, and despite the U.S. intelligence reports about Moscow’s ties to Islamic terror and the false flag attacks on Moscow, President Bush took his own path.

“This was a very good meeting. And I look forward to my next meeting with President Putin in July. I very much enjoyed our time together. He’s an honest, straightforward man who loves his country. He loves his family. We share a lot of values. I view him as a remarkable leader. I believe his leadership will serve Russia well. Russia and America have the opportunity to accomplish much together; we should seize it. And today, we have begun.”

The Western press asked hard questions after Bush and Putin made their separate remarks. It was a question directed at Putin, which led to a pivotal moment in U.S.-Russian relations.

“A question to both of you, if I may. President Putin, President Bush has said that he’s going to go forward with his missile defense plans basically with or without your blessing. Are you unyielding in your opposition to his missile defense plan? Is there anything you can do to stop it? And to President Bush. Did President Putin ease your concern at all about the spread of nuclear technologies by Russia, and is this a man that Americans can trust?”

Bush directed the question to Putin first, and when the question of trust was addressed, the Russian President said, “Can we trust Russia? I’m not going to answer that. I could ask the very same question.”

There was a brief but awkward pause caused by Putin’s response, with Bush breaking the sudden tension.“I will answer the question. I looked the man in the eye. I found him to be very straightforward and trustworthy. We had a very good dialogue. I was able to get a sense of his soul, a man deeply committed to his country and the best interests of his country. And I appreciated so very much the frank dialogue. There was no kind of diplomatic chit-chat, trying to throw each other off balance. There was a straightforward dialogue. And that’s the beginning of a very constructive relationship. I wouldn’t have invited him to my ranch if I didn’t trust him.”

Russian troops stand over a mass grave in Chechnya – February 2000

Credit – Natalia Medvedeva – Creative Commons 3.0

During their private meeting, Bush and Putin discussed Chechnya, Dagestan, and Russia’s response to Islamic terrorism, among many other topics. Putin was right to refuse to answer the trust question because he wasn’t negotiating honestly. Over a year ago, Putin cut another deal with the Chief Mufti of Chechnya, Akhmad Kadyrov. The Armed Forces of the Russian Federation had completed the first phase of its occupation of Chechnya in June 2000, and Putin named Kadyrov the head of the administration of the Chechen Republic.

For Al Qaeda, which was at its apex of power, this was the ultimate betrayal.

Next installment: A second wave of Islamic terror spreads across Russia, and this time, the attacks are real. The Second Chechen War continues for another eight years. Osama bin Laden’s influence fades, and Al Qaeda fractures. The ISIS caliphate rises and falls as Syria becomes the next Russian battleground.