BIPOC

A $2.5 trillion transfer of wealth will begin on January 4 if Congress doesn’t act

Up to 40 million Americans are facing eviction, foreclosure, and homelessness while investors wait to swoop in.

To many Americans, Gia and her husband (they requested we only use first names) live the American dream. Gia works as a substitute school teacher, and her husband is an international business consultant after a successful career at a Fortune 100. They own their home in a city that sits on numerous best places to live lists, and their children go to one of the top-rated public schools in the country. It seems so perfect, but Gia and her husband live a COVID nightmare and, like nine-million other American households, are on the brink of foreclosure.

A crisis, initial action, and then paralysis

When COVID related shutdowns swept the country in March of 2020, U6 unemployment skyrocketed to 18.1%. Even before the public health and financial disaster, 40% of American families didn’t have $2,000 in emergency savings, let alone the 60 to 90 days of living expenses financial planners recommend. COVID wiped out entire industries such as hospitality, travel, and theater and entertainment. For those in the service industry and gig economy, the slowdown has hit the hardest.

In response to the looming economic collapse, Congress passed the CARES Act, which included a one-time stimulus check of $1200 for some Americans, the Payroll Protection Program (PPP), and a moratorium on evictions and foreclosures. Despite trillions in aid, gaping holes remained that Main Street and American families have fallen through. Banks did not get guardrails on how to manage forbearances. Congress didn’t waive rent, only deferred it, and didn’t provide any financial support for small landlords. Twelve-million American households find themselves more than $5000 behind on rent, and six-million households face foreclosure.

Congressional leaders and the White House have agreed in principle that another stimulus package is needed, but hyper-partisan politics has destroyed any forward progress. In 20 days, the CARES Act and all of its protections evaporate. If Congress takes no action, the transfer of $2.5 trillion in wealth to large scale investors, private equity, and large corporations will begin.

Up to $4 trillion in cash awaits for the foreclosures and evictions to begin

At the start of 2020, private equity firms were sitting on $2.5 trillion in cash. They call it dry powder, money ready for investment where the quants feel the best ROI awaits. By some estimates, there is now as much as $4 trillion on the sidelines. Interestingly, savings have grown in the United States across all income brackets in 2020. However, for the 40% of Americans who live paycheck to paycheck, small business owners, and small landlords, dry powder is just a banking term.

Gia and her husband have a first and second mortgage on their suburban home. When COVID struck, and the region moved to remote learning, her work evaporated. As COVID ravaged the United States virtually unchecked, a U.S. Passport would get you into less than 25 nations. Her husband’s work came to a halt, and he became stuck in Italy for four months. Gia applied for unemployment in July but is stuck in administrative limbo with thousands of other Washingtonians, owed back payments.

Then a lifeline appeared, and Gia’s husband got a job opportunity through a friend in Italy. With travel restrictions easing, he traveled to his new job, and Gia was rehired as a substitute teacher. The light at the end of the tunnel flickered out quickly. A health crisis struck her husband, leaving him stranded, unable to work or travel.

Small landlords on the brink of destruction

Rick is a small property investor in Tacoma, Washington (Rick asked we do not use his last name). He was able to earn a living by flipping homes one at a time, but as he started to approach retirement age, he wanted to create a small passive income stream. In November of 2019, he bought a distressed fourplex on a nine-month loan. Part of the conditions was to rehab the property and secure four paying tenants by August 2020. Rick purchased the property with all the units rented, and he started to work with the tenants to end their leases equitably. Then COVID hit.

Part of the eviction moratorium requirements is renters need to prove they have no other place they can live. One tenant moved out in February, but the other three stayed on. In June, two more accepted cash for keys as a compromise, but Rick was already in trouble. Meeting his loan conditions was an impossibility.

“I believed they would work with me,” Rick said, “historically, these lenders will work with you. Now I’m being charged 25% interest, and it is impossible to make those payments.” One of the original tenants remains almost a year later. They are paying rent of $800 a month but claim they have no other place to live and have refused cash for keys offers. An attorney told Rick that for $10,000, he would get the renter evicted, moratorium or not, but Rick wants to be fair.

Rick’s lender moved to foreclose. His attorney was able to stop the action, but the lender filed a default, which prevents Rick from securing financing anywhere else. “My lawyer told me they are operating as a loan to own. They give me the loan, but they end up owning the property.”

The United States needs at least seven-million more affordable housing units than what is available today. Although rents in cities like Seattle have declined by 20% in 2020, property values have skyrocketed. Large investors have access to tax programs and incentives that aren’t available to small landlords.

Because rent is considered passive income, small landlords do not have access to PPP loans. The imminent foreclosure and eviction crisis will not only put millions of Americans on the street during a pandemic but will gut mom and pop landlords on Main Street.

For millions of Americans who are still paying rent, there is a hidden crisis in 2021. As small landlords lose their homes, these renters will get eviction notices from hedge funds and banks, with no interest in working with them to make sure they don’t end up homeless. For the remaining tenant at Rick’s quadplex, come January, they’ll face a forced eviction when the lender moves to foreclose.

Up to 40 million Americans face financial disaster in January, and 80% of them are BIPOC

The CARES Act and all of its provisions will expire on December 31, 2020. For the unemployed, the first blow will come between December 25 and 27, when it becomes the last day to collect extended unemployment benefits. The loss of unemployment for 12 million will put another three-million households in jeopardy of eviction or foreclosure. For another 18 million homes, back rent and forbearances will come due on January 1, 2021, and the courts will be open for evictions and foreclosures on January 4.

Gia’s husband’s job in Italy was helping shut down a hotel impacted by the COVID crisis. During his time off, he suffered a sports injury. What started as a headache evolved into blurry vision and searing pain. A doctor’s visit revealed he had a detached retina in one eye and an injury to the other. He needed immediate surgery to prevent losing his vision. His vision is still blurred, and he is required to spend most of his time supine. He cannot work, and he can’t fly back home due to the air pressure change. With only Gia’s limited income, the forbearance on their mortgage looms large.

Almost six-million Americans expect to lose their homes in the opening days of 2021. According to the Aspen Institute, 80% of those facing foreclosure and eviction are Black, Indigenous, or Persons of Color (BIPOC). For white households in America, the average net worth is $170,000, while for Black families, it is $17,000. This inequity can’t be explained away by education, income, or indebtedness. For white Americans, once they become homeowners, five-percent will fall back into renting. For Black Americans, the rate is double, at 10%. Black-owned small businesses had limited access to government aid programs, and by August, 40% of all Black-owned small companies had failed.

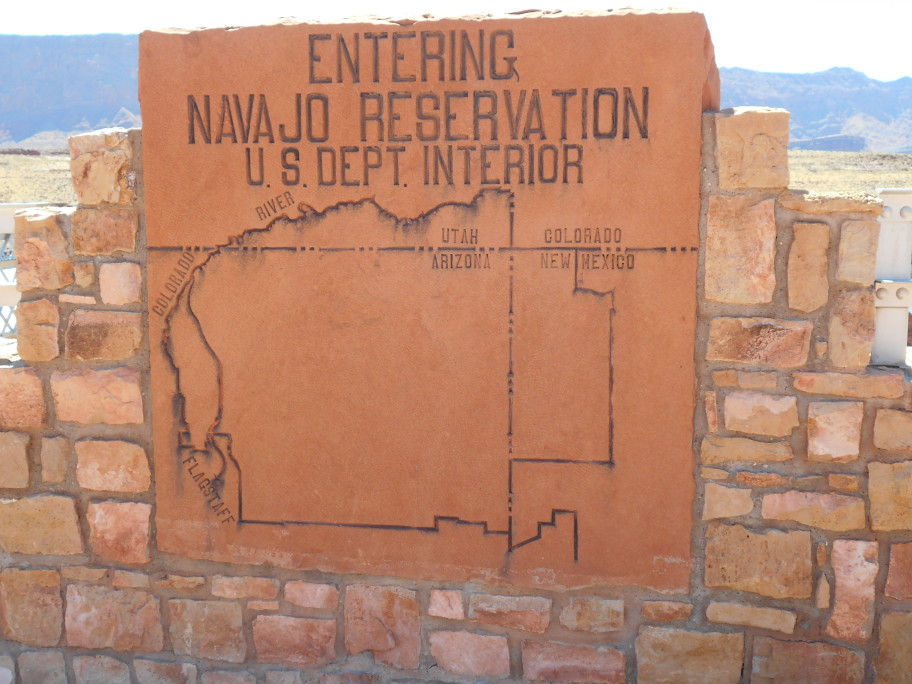

The BIPOC community has suffered the worst from COVID in near silence. Black, Indigenous, and Hispanic populations have higher rates of positivity, hospitalization, and death. This difference is driven by work in the service industries as “essential workers,” multigenerational households living under the same roof, and less access to quality healthcare. In Arizona, Doctors Without Borders have been operating on the Navajo Indian Reservation since April. When Indigenous peoples in Washington state appealed for PPE from the federal government, they were sent body bags.

BIPOC communities are more likely to be “needless delinquent.” Analysts estimate 400,000 American homeowners are eligible for forbearances on their mortgage but are not aware or have been given misinformation from their lender. For some of these struggling homeowners, the damage isn’t foreclosure but the destruction of their credit score. A lower credit score impacts interest rates, insurance premiums and can even be a barrier to getting a job.

What a $2.5 trillion transfer in wealth looks like

Gia and her husband have a first and second mortgage, and both are in forbearance. Their first mortgage is with Chase. Chase has taken the payments and interest they are skipping and moving them to the end of the loan term. Their second mortgage is with a small area bank, Umpqua. Umpqua will require them to pay one-and-a-half payments come January for six months. “When I explained our situation, the person at Umpqua asked how my husband had money to go to Italy. It was a business trip,” Gia explained. “I told them that we wouldn’t be able to meet those terms, and they told us they would put a lien on the house.”

Court systems from Boston to Seattle are bracing for a flood of forclosure and eviction filings. Here too, banks and large corporate property holders will benefit. With more legal resources and free cash to act, their cases will move to the front of the line. Mom and pop landlords will have to track their court cases independently, without a management company to oversee activity. Already facing a cash crunch, they’ll still have to pay court costs and lawyers fees, but that will only be the start of their problems.

The average American house has a value of $284,000. If nine-million households get foreclosed in 2021, that represents $2.55 trillion in property dumped into the market. As we learned in the Great Recession, some of these properties will go into bank possession and be allowed to crumble, unoccupied. Other properties will face gentrification, with family homes replaced by luxury units built to the lot lines. For others, like Gia and her husband, they’ll sell before the foreclosure hammer comes down and move further away from Seattle, seeking lower housing costs. The transfer of wealth doesn’t stop there.

For the 12 million households facing eviction, the looming crisis is even worse. An eviction on a credit report is a barrier to permanent housing, requiring large deposits. They’re facing thousands in debt and potential judgments with interest they can’t pay. An eviction can be a scarlet letter for years, becoming a barrier to buying a car, getting a job, or buying a home.

Although it may appear to be a boom for landlords with 12 million families hitting a rental reset button, this isn’t the case. For many, the door to another rental will be closed. Landlords may evict a family who can’t pay the rent, only to find applications from families who were just evicted.

Millennials in high-paying office jobs are already leaving the rental market for the suburbs to escape COVID restrictions and get more space for a home office. For those with money, decreasing rents will be a boom. Large investors can amortize shrinking rents and use tax vehicles to lower their expenses. Mom and pop landlords will face a further reduction in their passive income, driving even more homes into sale and foreclosure.

A cycle where renters will face an uncertain future of eviction through foreclosure or the sale to large investors could continue well after 2021. Affordable rentals in need of rehab will be gentrified, putting accessible housing further out of reach.

Congress has no financial incentive to stop this nightmare. For both parties, lobbies, PACs, and dark money keep congresspersons and senators in their positions of power. For the 40% of Americans who live paycheck to paycheck, there is no lobby to bend representative ears and grease the palms.

The reality is if this financial disaster is not averted, the 18 million households on the brink could be the tip of the iceberg.

The human cost

Ten-percent of the U.S. population is facing homelessness in 2021 if Congress does not act. Worse, an eviction moratorium extension only kicks the problem down the road, and the amount owed in back rent keeps growing.

The immediate need for the unhomed will be to get them homed as soon as possible. Families that end up on the streets for six or more months enter into chronic homelessness. The stress and anxiety of living on the streets take a psychological toll creating anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Long-term homelessness leads to self-medication, alcoholism, and drug addiction. In the middle of a pandemic crisis, there are fewer shelter beds available, and often families are broken up and have to give up their pets. Education for children is disrupted and made even more complicated in an era of remote learning, which requires a computer and access to reliable high-speed internet.

With up to 80% of those facing eviction and foreclosure being BIPOC, an entire generation faces the gutting of accumulated wealth. The barriers to creating generational wealth, particularly in the Black community, will fuel inequity for decades to come.

For Rick in Tacoma, he fell through a loophole created by the eviction moratorium. When he bought the property in November of 2019, he worked to do the right thing for his tenants. Although the one remaining tenant is employed, paying rent, and not impacted by COVID, they refuse to vacate the property using the moratorium as a barrier.

“The bad things about laws that are too broad; they don’t capture all the cases. In this case, COVID has nothing to do with this one tenant,” Rick lamented. “I contacted the state Attorney General office, but they said they had never heard of a situation like this and didn’t know how to proceed. I told them that just a letter or a phone call to the lender would help, or provide a help desk for basic assistance, but the government doesn’t work that way.” Rick’s end game appears to be the loss of a lifetime of work, destroyed credit, and no possible retirement.

Gia is waiting for the day when her husband can return from Italy, and they plan to put their home on the market. At the start of 2020, they were on a solid footing with a nine-month cushion. “How could you plan for this,” she asked.

An immigrant herself, Gia arrived in the United States as a child at the end of the Vietnam War. “The [United States] took them us in with open arms back then. You want to escape Communism? Sure!” she reflected.

“We grew up, and we were on food stamps for a while, and there were five brothers and sisters. They put us in low-income housing, but we got out. Mom and dad bought a home. He was a mechanic and put six children through college.”

“We have to care for our citizens. What are you going to do with these people who have nowhere to live? No transportation. No housing. No medical care. Where are people going to go?”